Andy Warhol was an inspiring, exciting, and interesting fella. As such, he attracted a group of similar people. Eccentric and fabulous, the whole world was enamored with not only him, but his group of “superstars”, as they came to be known. One of these girls was Edie Sedgwick, whose fashion legacy lives on today. (”Factory Girl” the recent movie starring Sienna Miller, is tantamount to her prevalence in society, even now, and the onslaught of similar styled clothing in retail chains such as Forever 21 and Urban Outfitters.)

I thought it worthwhile to explore the history of this beautiful & tragic woman whose life fascinated so many, especially as tomorrow is our “Girls Night Out” party, the final big party celebration of our Andy Warhol exhibit! Marie Claire did a wonderful article on Ms. Sedgwick, chronicling her ups and downs. Here the article is in its entirety, for your reading pleasure:

Style icon Edie Sedgwick inspired the likes of Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan and left behind a fashion legacy that still lives on today. Camilla Morton charts the all-too-brief life of a swinging ’60s It girl and true individual.

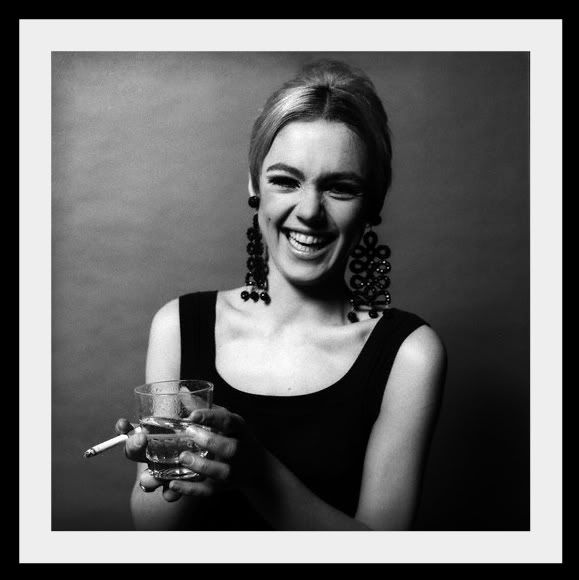

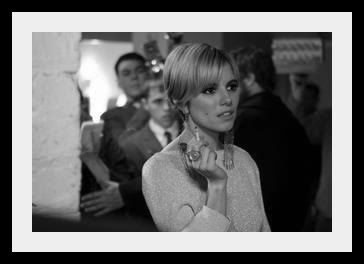

Sienna Miller as Edie Sedgwick.

New York, 1965: a gamine bottle blonde walks through the crowd of hip young things. With her thick, black kohl eyeliner, bouffant hair and antique chandelier earrings dripping priceless jewels, she emanates style. No-one has ever seen anything quite like this young woman, who wears nothing more than a leotard, opaque tights and a sweater.

Men and women stare at her with open admiration - the women making mental notes to try out her look at home. She is the epitome of the swinging ’60s scene and one of the architects of the beatnik style. Part muse, part model, sometime actress and wild society girl, she is Edie Sedgwick - and in her short life, she will become a legend …

Sedgwick would go on to inspire the likes of Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan, but in a life that lasted just 28 years, she also suffered from an eating disorder, squandered her inheritance, and battled drug addiction and mental illness. Yet her influence continues today - from the Christian Dior catwalk show dedicated to her look to the film Factory Girl, featuring Sedgwick’s latest style apprentice, Sienna Miller, it seems the legacy of one of America’s first It girls will live on for years to come.

In many ways, Sedgwick never had a chance at a stable life. She was born Edith Minturn Sedgwick on April 20, 1943, in Santa Barbara, California. Her father, Francis Minturn Sedgwick, was a rancher and sculptor who had three nervous breakdowns prior to his marriage to Alice Delano de Forest, an heiress. His psychiatrists advised the couple not to have children because of Francis’s manic-depressive psychosis. They had eight: Alice (Saucie), Robert Minturn (Bobby), Pamela, Francis Minturn Jr (Minty), Jonathan, Katherine (Kate), Edie and Susanna (Suky).

Although the Sedgwicks appeared to lead an idyllic life on their various Californian ranches, appearances were deceptive. “We were dressed in hand-me-downs from our cousins, and we got very little for Christmas or birthdays,” Saucie later recalled. And Francis was an oppressive and tyrannical father. “He was always trying to sleep with me, from the age of about seven,” Edie once claimed.

The young girl had very little exposure to “normality”. She and her siblings attended their own tiny school, and rarely left the ranch. Their bizarre home life soon took its toll. An alcoholic by the age of 15, Minty was admitted to a psychiatric hospital in his 20s after he was found in New York’s Central Park making a speech from a statue - to a nonexistent audience. He hanged himself the day before his 26th birthday. Bobby, too, had inherited the family predisposition to mental illness, and was escorted from his Harvard University dorm in a straightjacket. After several stints in mental institutions, he died in January 1965, when he crashed his Harley-Davidson motorcycle into the side of a bus on New Year’s Eve.

Edie developed an eating disorder at an early age. Her problems only intensified when she stumbled upon her father and another woman “humping away”. Francis accused his daughter of lying and had her put on tranquillisers. Consequently, the teenager became addicted and withdrew into herself. Francis gave Alice an ultimatum: put Edie in a psychiatric hospital or he would leave. His daughter was sent to Silver Hill Hospital in 1962.

Her weight plummeted to 41 kilograms, so she was moved to a closed ward. Treatment helped, but there was more trauma to come when she was on leave from the institution. She later revealed: “I met a young man from Harvard … That was the first time I ever made love.” Sedgwick fell pregnant, and was persuaded by her doctors to have an abortion. “It kind of screwed up my head,” she said.

Following her release from hospital in the autumn of 1963, Sedgwick moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she studied art at Harvard. Surrounded by men such as dandified graduate Chuck Wein, she quickly established herself on the social circuit and became the doyenne of the gay scene. In 1964, she turned 21 and came into a trust fund. Life was finally looking brighter.

With the help of Wein, Sedgwick moved to New York, where he planned to promote her in the ’60s art scene. “He knew that she had this quality, but that she was very disorganised and wouldn’t be able to pull it off by herself,” said friend Sandy Kirkland.

The city offered the distractions that Sedgwick craved. Part of her unique appeal lay in her ease at moving between different social groups, and soon after her arrival in New York, she attended a party held by producer Lester Persky, where a friend introduced her to artist Andy Warhol. “Why don’t we do some things together?” he asked her. Sedgwick was about to hit the big time.

Warhol was one of New York’s leading lights and became famous for his iconic pop art. In his studio, known as The Factory, he gathered together like-minded artists to create underground films, music and art. He was captivated by Sedgwick’s old-money heritage and artistic energy, and she was soon admitted into Warhol’s inner circle.

Sedgwick’s unique fashion sense flowered in the rebellious avant-garde atmosphere. She would wear her grandmother’s jewels with a long dress and bare feet. Opaque tights, leotards, false eyelashes and chandelier earrings became her signature pieces.

Punk-rock legend Patti Smith recalls her reaction to seeing a magazine photograph of Sedgwick, clad in a black leotard and a boat-neck sweater. “She was such a strong image that I thought, ‘That’s it.’ It represented everything to me, radiating intelligence, speed, being connected with the moment.”

Celebrity milliner Stephen Jones identified something radical in Sedgwick’s demeanour: “Iconic society women had always been demure and elegant. Sedgwick was downtown not uptown, active not passive, sunglasses not ball gowns. Her look was a mixture of sweet and sour; an angelic face distorted with bleached hair and disfiguring make-up. You could call her the first punk.” In contrast, the rumour that she never took off her make-up, instead adding a new layer every day, suggests a fragility underlying her bold image. In 1965, Warhol cast Sedgwick as an extra in his underground film Vinyl. Besotted with her striking looks as much as her screen presence, he commissioned further scripts for her - Kitchen, Poor Little Rich Girl, Beauty #2, Outer And Inner Space - establishing her as his “Queen of The Factory”. For the next year, the pair, dressed in matching striped jumpers, were inseparable. Sedgwick even dyed her hair silver to match Warhol’s.

Ultimately, her intense but platonic relationship with Warhol was short-lived. By 1966, Sedgwick’s fashion sense had been picked up by the mainstream. She modelled for Vogue, who described her as “white-haired with anthracite-black eyes and legs to swoon over”. She also became designer Betsey Johnson’s first fitting model. “She was very boyish; in fact, she was the very beginning of the whole unisex trip,” said Johnson.

Sedgwick had also met and become infatuated with Bob Dylan, despite starting an affair with his right-hand man, Bobby Neuwirth. “Somebody who knew Sedgwick said, ‘You have got to meet this terrific girl,’” recalled Neuwirth. “Dylan called her, and she chartered a limousine and came to see us.”

At the time, Dylan was living in the Chelsea Hotel with his future wife, Sara Lownds, and her three-year-old child from a previous relationship. He was also having an affair with folk singer Joan Baez, who only ended it when she discovered him in bed with Lownds - whom he’d neglected to mention.

Sedgwick was flattered by Dylan’s interest in her (a picture of her appears on the album sleeve artwork of his 1966 Blonde On Blonde album, and it’s said that two songs on it - “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” and “Just Like A Woman” - were inspired by her). But the young socialite was devastated when, in February 1966, Warhol bitchily informed her that Dylan had secretly married Lownds the previous November. Crushed, Sedgwick announced that she was leaving The Factory.

By this point, she had spent her entire trust fund and was broke, alienated from the Factory crowd, and increasingly dependent on speed and heroin. Vogue refused to endorse a model identified with the drug scene, and having accidentally burnt down her Manhattan apartment, she moved in to the Chelsea Hotel.

The glamorous world Sedgwick had dominated had evaporated. At Christmas, she sought refuge at home, and her brother Jonathan described her as “a painted doll, wobbly, languishing around on chairs, trying to look like a vamp”. A lifeline was offered in 1967, when Chuck Wein cast her in the film Ciao! Manhattan, but the prevalence of drugs on set only hastened her descent into mental illness. She went AWOL from the movie before finishing it. Finally, the long-suffering Neuwirth could take no more, and left her. Sedgwick was devastated. “I felt so empty and lost that I would start popping pills,” she said.

At the same time, Sedgwick’s father became seriously ill. Before he died of pancreatic cancer in October 1967, he appeared to show some remorse for his parental shortcomings, saying, “My children all believe that their difficulties stem from me. And I agree. I think they do.” Friends hoped that Francis’s death would relieve Sedgwick of some of the burdens she had been carrying since childhood, but instead, it seemed to weigh her down further.

Slipping in and out of hospital, Sedgwick was spiraling out of control. In 1968, the New York Post asked: “Whatever happened to Edie Sedgwick?” Warhol was quoted as saying, “I don’t know where she is. We were never that close.” By 1969, she had been arrested for drug possession and was admitted to a psychiatric unit. There, she found support in fellow drug addict Michael Post and, under the supervision of two nurses, even managed to complete the filming of Ciao! Manhattan, including several sequences where her character receives electric shock treatments. Over the next two years, she would undergo more than 20 shock treatments in real life - at the same clinic used in the movie.

By 1971, it appeared that Sedgwick had begun to turn her life around. She married Post in July of that year, stopped drinking and worked hard to limit herself to drugs for pain relief. On the night of November 15, she was filmed at a fashion show at Santa Barbara Museum, looking fit and healthy. That evening, a palm reader grabbed her hand and was shocked by her short lifeline. Sedgwick calmly replied, “It’s OK, I know.”

But she couldn’t have known how quickly the end would come. At a party after the show, a guest verbally attacked her, calling her a heroin addict. Sedgwick became hysterical, so Post took her home. She took her prescribed medication and fell asleep.

The following morning, Sedgwick was dead. She was 28 years old. The coroner registered her death as an accident/suicide due to barbiturate overdose.

Sedgwick and Warhol were never reconciled. On hearing of her death, he wondered out loud if her husband of a few months would “get her money”. He was curtly told by a friend, “Edie didn’t have any money. She spent it all on you.”

But neither Warhol nor Sedgwick could ever have predicted the influence her unique style would continue to have, from Kate Moss’s pixie haircut in 2001 to John Galliano’s 2005 show for Christian Dior. In the end, Sedgwick’s lasting legacy is her individuality, not her unhappy private life.

“Edie danced to her own tune, and I imagine this is what inspired Warhol and Dylan as much as it did me,” said Galliano. “She created her own identity … She may only have had 15 minutes of fame, but her style and image influenced a whole generation.”

She is my inspiration for the evening, as I will be wearing the black tights she made so popular, the always classic boat-necked striped t-shirt, and chandelier earrings. You should come out too— dressed in your best 60’s and 70’s outfit! Click for more information on the event– we can’t wait to see you there! We will rock out to the music of the times, and have games, drinks, and food to boot!

Correspondence schools flourished in the inter-war period. Dressmaking and millinery courses in particular were embraced by women who wanted the new fashions but couldn’t afford retail prices. Many women turned to fashion as a vocation in order to support their fatherless families or to earn extra income to spend on the new luxuries. Working women also embraced the relatively inexpensive ready-made clothes as mass production of contemporary clothing became common.

Correspondence schools flourished in the inter-war period. Dressmaking and millinery courses in particular were embraced by women who wanted the new fashions but couldn’t afford retail prices. Many women turned to fashion as a vocation in order to support their fatherless families or to earn extra income to spend on the new luxuries. Working women also embraced the relatively inexpensive ready-made clothes as mass production of contemporary clothing became common.